Today I discovered that the FBI released a public service announcement and website on how to attempt to survive a mass shooting. The FBI. The biggest law enforcement agency this country. It’s not even new; it was released three years ago, and just happened to hit my feed today.

Run. Fight. Hide.

If this messaging sounds familiar, there’s a reason for it.

American politics and policies have long put the onus on the victim to protect and defend themselves. It didn’t start with active shooter drills in elementary schools. Gay folks in the armed forces were taught that they could avoid sexuality-based violence if they kept their mouth shut. Women have been taught for decades how to avoid getting sexually assaulted. Black families have taught their children how to interact with cops so they don’t end up jailed or killed.

Systemic issues should not place the burden of safety on the individual. And yet, here we are.

This country was built on the blood and bodies of innocents. The colonizers didn’t see indigenous people as people. Still don’t.

This country was built on the backs and by the hands of people stolen from their homes and enslaved across oceans. The slavetraders didn’t see black people as people. Still don’t.

This country was built on the unseen labor of women and fertile wombs. The patriarchs didn’t see women as people. Still don’t.

This country was birthed from violence, and begets, and begets, and begets.

“It could never happen here.” It could. It has. It does. It will.

Four years ago, I was in the minority (along with my public health friends) who were aware that this country was not prepared for a pandemic. You can’t shoot a virus, so I guess there wasn’t much funding.

Twenty years ago, I didn’t live with the weight that any day, in any public or semi-public place, I could be a victim of a mass shooting. Columbine was supposed to be a once-in-a-generation tragedy. So was the Oklahoma City Bombing. So was 9/11.

It has been going on so long I don’t even want to say that it isn’t normal. Because now, it is.

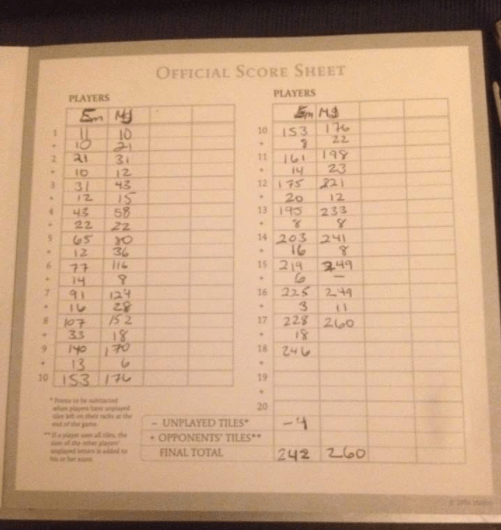

In my line of work, we like to use simple visual tools to convey big ideas (stay with me here). The one that comes to mind is from OSHA, the organization responsible for ensuring occupational safety. Here it the hierarchy of controls, courtesy of Wikipedia:

Can you see where we are on the chart? Where marginalized folks have been for generations?

We are at the personal protective equipment level.

The hazard has not been removed. It will not be.

The hazard has not been replaced. It will not be.

People have not been isolated from the hazard. They won’t be.

The way people operate their day-to-day lives has changed, it can be argued; but not for safety, not on a societal scale.

We are at the point of the triangle, where the individual must accept that no one in power is going to do fuck-all for them, and it is their own responsibility to survive the violent actions of other individuals.

I’m not saying it’s not an important video and message to get out; I’m not saying it won’t save lives. It will. My point is, even though it shouldn’t have to, there are not enough people with enough money and enough power who can eke out a single fuck to give.

I don’t have a solution. Well, I have some ideas, but they keep getting squashed in the hallowed halls of the government. Call this a rant, call this screaming into the void. The video tonight just made it crystal clear that, for some time now, I’ve understood that on any day, it could happen here. And you know what bothers me about that, is how matter-of-fucking-fact it was. Just like, oh, might rain on Thursday. Might cause traffic problems. Might get shot while doing the grocery shopping this week.

And it’s coming out like this, rage pouring through my fingers, as I sit here knowing my daughter is sleeping soundly having no goddamn idea about this yet in the next room. It breaks my heart and strengthens my resolve that I know all too soon, she, too, will learn that she might be next.

Check out the video if you have the bandwidth. My daughter will learn how to stop the bleed. How to run, hide, and fight.

May that she, and you, only ever know the fear of it happening and not the reality.