There’s always music on in this house. Always sound. For now, for these morning hours on this day, it is as silent as it will ever be. Lucy is at a friend’s house, waking up soon at a sleepover before spending the day with the sitter. TV is off, there’s no music; every single device on silent. The dog sighs occasionally, the cars pass outside the window. It’s early enough on a Saturday that the general sound of two men having a conversation across the street carry over. I’ve opened the window, the first time in months; there is no breeze, and the shade is still deep. I’ll have to remember to close it soon and turn the AC back on.

Seven years ago, time stopped somewhere on Tuesday morning, July 17th and didn’t start again until 6:34AM on Thursday, July 19th. The time between exists only as a liminal space, a time hung in the balance of disbelief.

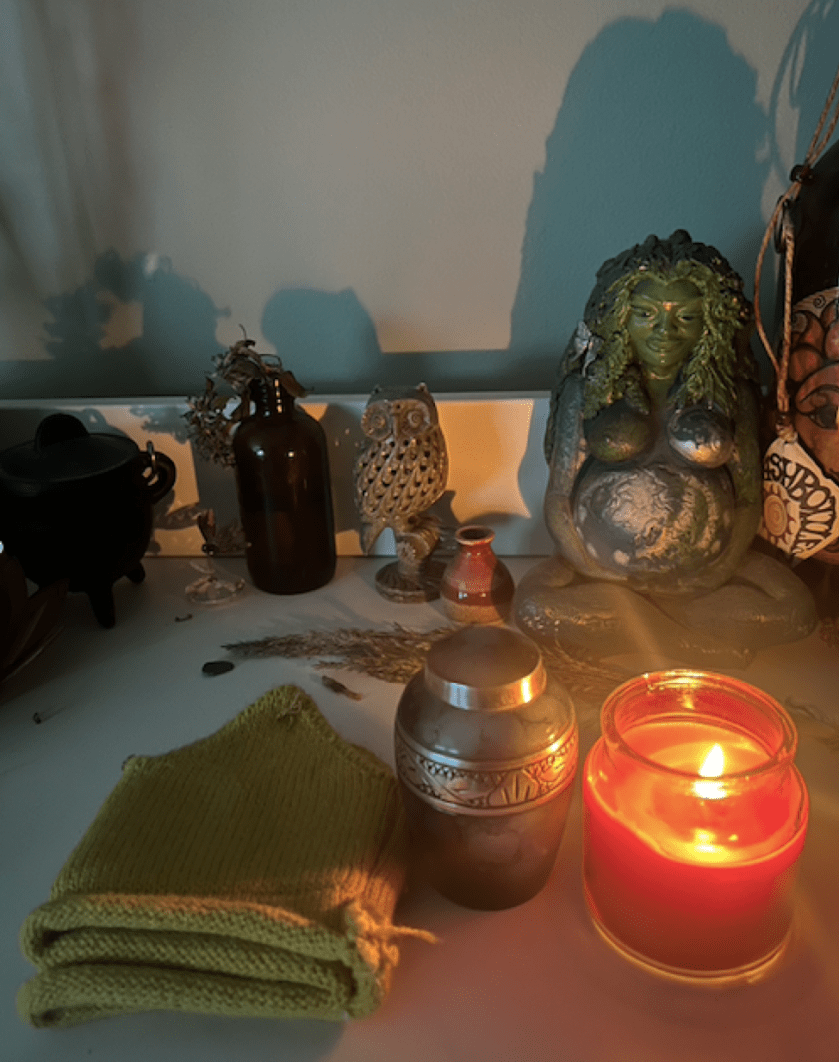

Today, at 6:30, I held the tiny urn to my chest, cold stone, until it was warmed through, and I felt the cool patches from where I had given it my warmth. I set it next to his crown, then struck a match; the tiny stick splintered, enough fibers holding together that the flame didn’t fall. I lit the candle, the one given to me by someone else who had similarly birthed stillness, and sat. The Mother watched over, her face serene in the candlelight.

I spoke to him for a minute, words so similar to what I tell Lucy – I love you so much. I’m so proud to be your mama. I love you, I love you – and more that I hope never to say for Lucy – I miss you every day.

My body knows the time without checking my watch. My whispers trail off, and I let the minute of his birth pass in silence, acutely aware of the emptiness of my hands and my womb. They ache for the tiny life they once carried.

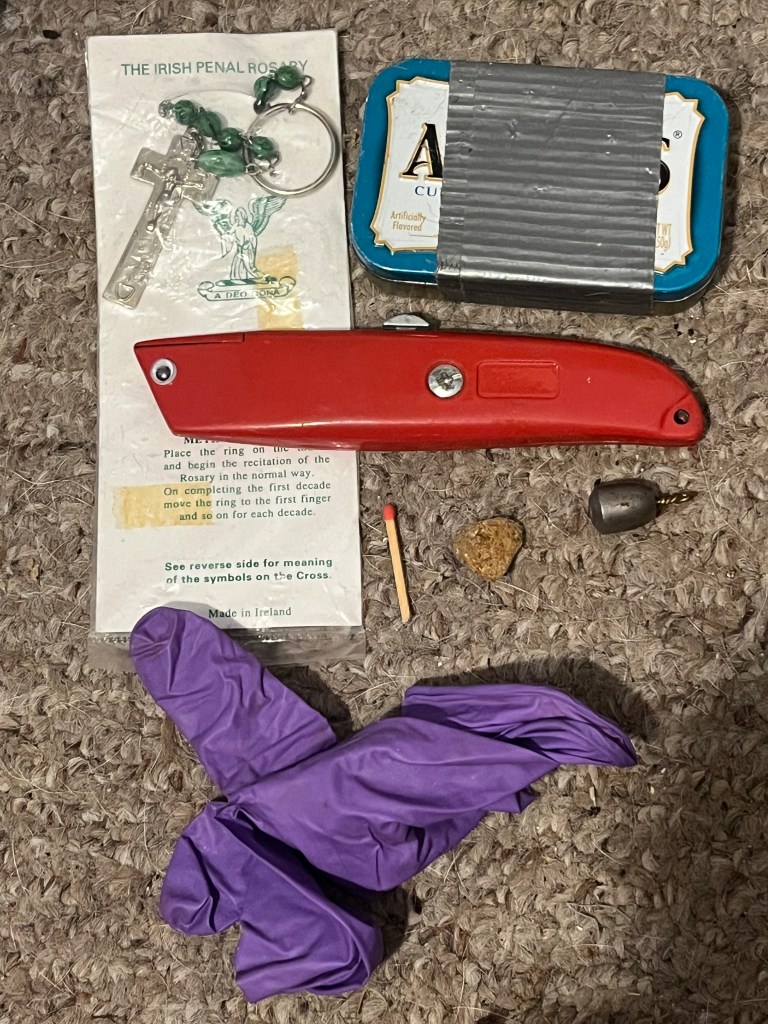

Then I rise, and gently lift the baby blanket his Nana made, the only thing I have left that held him besides my own skin. I opened my phone and pulled up the video of Andrea Gibson reading their poem “Love Letter from the Afterlife” to their wife. I let it play, feeling the words echo in the empty parts of me. “One day you will understand. One day you will know why I read the poetry of your grief to those waiting to be born –“

The playback stopped. I looked over at my phone, laying on the bed. The video was still up, so I didn’t move, just closed my eyes. Waited.

Waited until my body sobbed, unbidden, and I reached for the phone. I picked it up without touching the screen, and –

“ – and they are all the more excited.”

The mortal death of Andrea Gibson hit me hard this week, in this space between Hawthorne and Oscar’s birthdays. They left right smack between them – 9, 14, 19. I can’t ignore the symmetry of those dates strung together. I haven’t written since their death, but I’ve felt it coming, the words building up behind a dam made from capitalism and parental responsibilities. Apparently now is when the dam breaks.

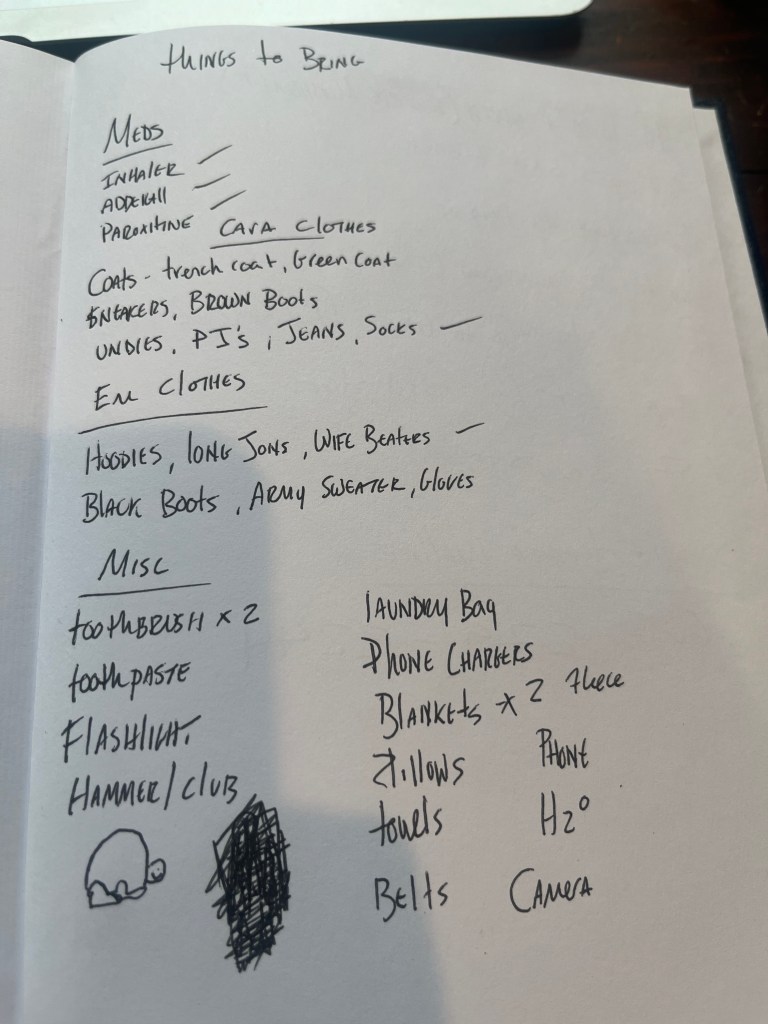

Every year, I try to be gentler with myself in this between time. I liken it to the days between Christmas and New Year in workplace. There’s no deadlines, no major work being done – I know that’s not true for everyone, but in my world, the fiscal year is separate and tends to be when the rush of deadlines hits. And, in so many ways, it is a new year for me. Forget CE/BCE or BC/AD. Life is divided differently for me, and I think, for all those who have carried both life and death in their bodies. There is the Before Oscar time, and the After Oscar time. And so, when the clock strikes midnight tonight, The Year After Oscar 7 begins. I’ll return friends calls and texts, and get the weekly grocery shopping done. I will set the new year off with music in my soul-home state, and dance with my amazing, brilliant, feral child as it echoes off the lush green mountains. Hawthorne and I played that music for hours and hours for both of the little lives we shepherded. How fitting to find the concert there, ten miles from Lucy’s birthplace, on the first day of AO 7. It also feels a little strange to think that’s what I’ll be doing merely 36 hours from now, from these moment of heaviness that drag my fingers to the keyboard to catch everything that is pouring out of me faster than the pen can. The reams of paper I already go through.

Seven years. I’ve written before how “should” is a four-letter word. He should be seven; he should be starting second grade a few days before Lucy has her first day of kindergarten. We should be shopping in West Lebanon for new clothes for them to start school in our tiny town of Stockbridge, Vermont. Should sucks.

Lately I have been feeling called to lean into my witchy aspects more. I started keeping my tarot cards closer, and being less prescriptive with my own self on when I use them. I’ve been reading more, and while I roll my eyes at the algorithms, enjoyed the content that’s crossed my feeds. I’ve been listening to my horoscope from an astrologer and witch I feel a connection to, and have finally done my star chart. But I find myself wondering, this year, about the symbolism and signs around Oscar. So, I did his star chart – and downloaded the full explanatory report, because again, I’m just learning. He’s a Cancer sun, like his Papa, that I knew; also Libra moon and Leo rising.

Today, he would be seven years old. Today, grief weighs seven pounds and one ounce, and is the heaviest it ever is. I’ve tried to explore numerology before to no avail, and today is no different. I feel no connection to it; maybe I don’t understand it enough, but today does not feel like the day to pursue it, either.

Today is a day to give myself the space to feel what needs to be felt, just like I did on Hawthorne’s birthday last week. That day I walked over 18,000 steps on the beach and on a hike at the (poorly named) World’s End park, and I found what I needed. Today I have some options after writing – writing is compulsory, after all – and whatever feels good, I’ll follow. Last week my therapist asked what containers I have for all this grief; how do I hold it? And really, the containers are the same as they have always been. Writing, and natural spaces where the air isn’t crowded with voices.

So if you see me today, just give me a wave. Leave a message at the tone, drop me a text or a DM, and just know that I’ll get back to you in the new year.