Content warning: This post is about my personal experience and history with non-suicidal self-harm. It’s not the first time I’ve mentioned this, but I believe it’s the first time I’ve got into this level of detail. If that’s not comfortable for you, for any reason, you don’t need to read on. It’s okay to skip this one.

Today is kind of a big deal, coming at the end of a year that was crowded with all sorts of joys and challenges. Today – a good friend’s birthday, fifteen years since my would-be wife kissed me – marks seventeen years since I self-harmed.

Humblebrag? Nah, straight-up bragging. I’m proud as hell of myself.

This is also the first year I remember self-harm (cutting, in my case) was acknowledged as an addiction. Prior to reading Bruce Perry and Oprah’s book, What Happened to You?, the only people who had ever called out the behavior as an addiction were two of my therapists. Every one of them was a fresh bandage on old wounds that I still feel; each one, a layer of validation I didn’t know I needed to hear.

When I call cutting an addiction, I’m not comparing it to other addictions. I’m using the term as good ol’ Merriam-Webster defines it: a compulsive, chronic, physiological or psychological need for a habit-forming substance, behavior, or activity having harmful physical, psychological, or social effects and typically causing well-defined symptoms (such as anxiety, irritability, tremors, or nausea) upon withdrawal or abstinence.

And yes, of course I’ve gone down the rabbit hole of the DSM-V and ICD-10/11 and found that self-injurious behaviors that are not precipitated by the use of a substance (one of the eleven listed, including caffeine, which seems awfully rude to me) are actually in a section called “Conditions for Further Study” of the DSM-V. They’re referred to as non-suicidal self-injury, or NSSI. And in my experience is a perfect fit. I didn’t cut because I was trying to die; I cut because it was the best way I knew to immediately feel like I didn’t want to die.

Seventeen years ago, I would have hit every point in the criterion – I engaged in it more than 5 days a year, I expected it would provide relief and create a positive emotional state, I had negative thoughts prior to cutting and I thought about it often, it was definitely not socially sanctioned, it was something I did to manage things across settings (ie, work, school, relationships), and it didn’t occur in the contest of psychosis or substance use.

I was not doing it for attention, as the therapists and psychiatrists in my teens told me and my parents. They had no idea of the extent. They only found out when I had a period of anxiety and happened to have a safety pin on me, and was absently scratching at my arm – not enough to do anything but turn the skin white. But a friend saw it and was concerned, and that’s how I ended up sitting in the psych hospital ER with my mom that afternoon. But it was something I had been doing – and hiding – since I was a child.

I remember being around six or seven, playing in the woods behind my house. If there were brambles, I’d run through them. I would try to throw stones and branches up and get an arm or leg under them before they came down. I loved the bruises and cuts and scrapes; loved how it would sting when I got in the bath, or ache when I pressed on the bruises. I did this. I felt this. It’s just for me. Everything about it was for me – my choice when and where and how. I think it was my first cognizant experience of autonomy; well, that will be fun to unpack with my therapist in 2026.

In order to keep it for myself, I knew I had to hide it – that, or explain it. I’m a terrible liar, so often, part of the build-up to cutting as I got older was, how can I believably explain this away if someone were to see it? Luckily, in a way, I figured out that I didn’t need to see the blood to feel the relief, to get that rush of endorphins that let my shoulders relax and my vision clear. I just needed to feel the pain from something sharp, and if there was something to keep the feeling going, all the better. I used a push-pin a lot – poking into the skin far enough for the sting and especially where I knew I’d get sweat in it later. No one was looking where I was using it – my scalp, behind my ears, the thin skin between my fingers and toes. When that wasn’t enough, I made sure to have a damn good explanation. Sometimes I’d blame it on sports – a branch I hadn’t dodged while running, someone hadn’t clipped their toenails in sparring. I blamed the cat once or twice, after she bit me and actually sent me to the ER with cellulitis in my hand – she’d scratch, too, and was an easy scapegoat. Shaving my legs was a good one, too. One of the last times I cut, shortly before I stopped, I said I’d slipped stepping out of the back of the ambulance, and managed to get a cut from the corrugated metal step.

My palms are damp, and my shoulders are tight as I write this. Why this is what I need to write right now, at the end of December when there are so many things I could share, I don’t know. But I need to, I suppose.

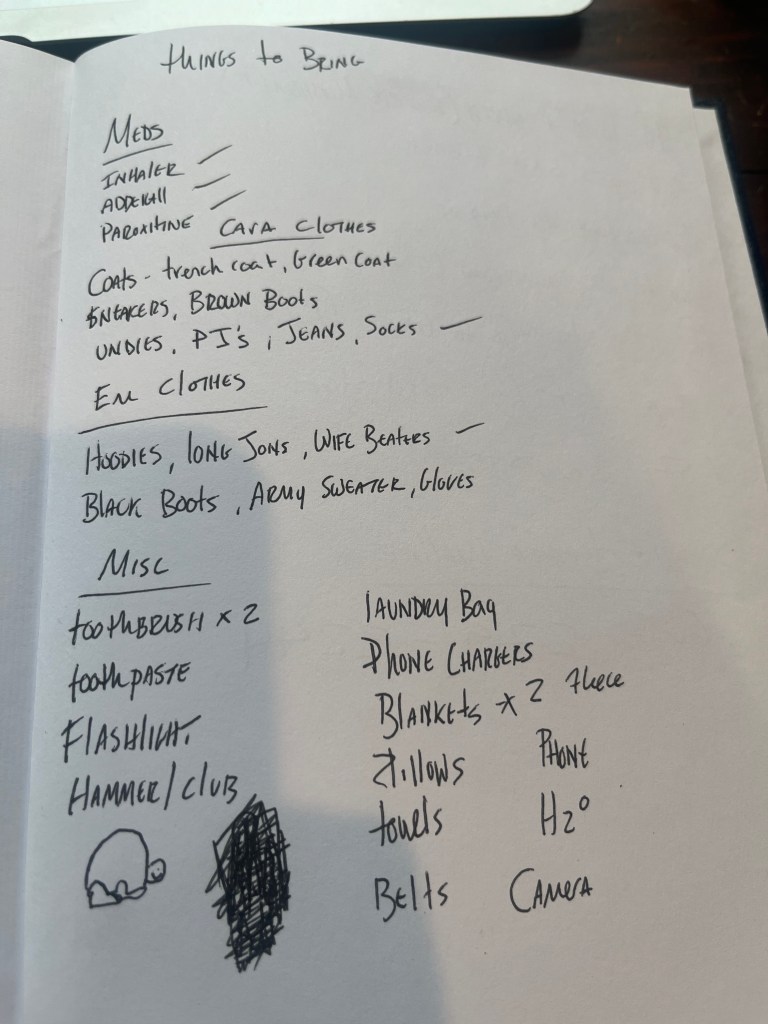

Seventeen years. There are some hard truths in those years – times when I came close, times when I thought I’d break the streak because of everything going on. Because, as readers of this blog know, in the past seventeen years, I’ve been through some shit. I’ve lost a parent, a child, a father-in-law, a damn good dog, and my wife. I’ve divorced, married, and been widowed. I’ve lost lovers and chosen family that I never thought I would. I’ve been officially diagnosed with ADHD, PTSD, anxiety, and many flavors of depression. I’ve had arteries in my neck dissect and put me at significant risk. I’ve left jobs and started new ones; I’ve given birth twice, and have the most amazing muppet of a six-year-old. I’ve written books and been rejected by agents. I’ve fought the IRS and gone to graduate school. I’ve lost my brakes while driving, and climbed (small) mountains. I’ve been living this one wild and precious life – not always to the fullest, but I’ve been doing it, and I’m going to keep doing it.

Do I miss cutting? Yeah, I do. Do I think about it often? Yeah, almost daily. In the words of the Goo Goo Dolls, scars are souvenirs I’ll never lose; the past is never far. I don’t have many – I was careful; I never needed stitches, and I rarely cut in dangerous areas or deeply. On this aging body there are four – three thick white lines, and one set of three small thin ones. I can remember each one in vivid detail. The little set I blamed on the cat; and one of the big ones was the time I “slipped” out of the ambulance I was working in. The other two I wasn’t living in a situation where I was making excuses anymore, and had no one to hide them from.

One of those scared me – I had cut way too deep. I felt, for the first time, that I wasn’t in control of the cutting. I know I had other marks on me then, too, but it was that one 2” gash that had me frightened enough that I ended up in ER. I didn’t need stitches, but spent five days in the locked psychiatric unit. I was discharged on a fistful of meds for depression that my ex encouraged me to stop taking because they weren’t helping, which lead to my first experience with venlafaxine withdrawal, landing me back in a different ER and needing sedation. My memory of that time is poor; and not especially traumatic, seeing as I remember little more than flashes. Enough that when I deliberately tapered off venlafaxine after spending six years taking it, my body remembered, and the taper had to be slowed and extended in order for my system to acclimate. PSA – If you ever want to stop taking venlafaxine, please do so with caution and medical provider support.

But that experience didn’t make me stop. I continued for another 21 months. Why? I mean, to my thinking at the time, why not? I had found the boundary and knew exactly how far I could go. I had no reason to stop. Even when my [then] husband begged me or ordered me not to, I just went back to hiding it, easy-peasy.

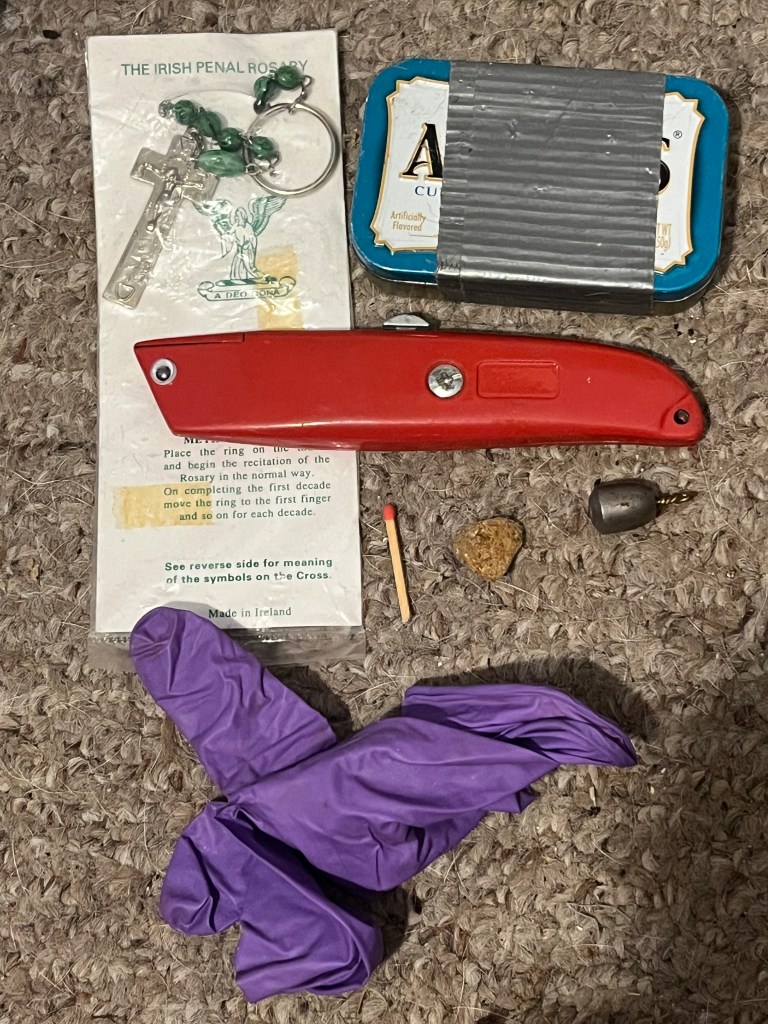

The final time came on December 28, 2008. We had just finished a call; I don’t remember the patient or the reason we were there, but there’s a clear moment I do remember. I was standing in the stall of a bathroom in the women’s locker room at Sisters of Charity Hospital in Buffalo New York, my boots on, the legs of my pants and long-johns shoved up to above my calf. Chest heaving, I looked at the Swiss army knife in my hand, the blood seeping from the fresh cut. I was in a bathroom stall, for fucks sake, in the middle of the goddamn night, cutting with an old knife that wasn’t likely super clean. I remember thinking, I don’t want gangrene. This would be a stupid way to lose my leg. And then, I don’t want to do this anymore.

I don’t know exactly what I did then; I’m sure I cleaned up and got back to work like nothing had happened, like every time before. Talked shit with my partner, got coffee from a 24-hour Tim Horton’s, and took another call.

After that, the first few months were touch and go. I got so close – got to the point of pressing the blade to my skin, but never moved it. I tried other ways to trick my brain, recommendations from reddit and from therapists. I used a red marker where I wanted to cut; I snapped a rubber band against my wrist; I used the back of the knife to lightly indent where I wanted to cut. They all felt silly to me. At the time, having a knife in my pocket at all times was important, so I didn’t feel like that was a solution either.

Eventually, it got easier. I indulged in the fantasy a lot – like, a LOT. Any time I wanted to cut, I let myself walk through it in my mind. And yeah, sometimes, I still do. There have been plenty of times where the only reason I don’t is I know that I would never hit this long of a streak again if I go back to it.

The desire is still there, the urge always simmering. It is a craving, sometimes far stronger than others, but never gone. I don’t use the rubber band or the red marker anymore, and if I’m not at work, still often carry a pocketknife. I’m still active; I probably could avoid thorns a little more, but hey, hiking in New England carries its own risks. Plus, I’d rather stand in the midst of them so I could lift the kiddo over them.

I’m able to identify and name the times when I’m feeling self-destructive, and I’ve gotten good at reaching out to people who can hear me say that and speak to those parts of me. In those moments, they remind me – just get through this night, and tomorrow you will get up and do it again. They’re right, and I do.

Looking into the DSM characteristics and the published literature of it has been interesting, too. I didn’t know NSSI is considered a “behavior specialty” for borderline personality disorder – luckily, something I’ve never been diagnosed or considered for. Most of the studies done are in the context of BPD, and when they aren’t, it’s with veterans or adolescents. Yes, I was an adolescent during much of the time I self-injured; if I estimate the time, it was a period of 16 years that I was consciously trying to hurt myself, though the method evolved over time.

Sixteen years of self-harm.

Seventeen years since the last time.

Next year, my abstinence from self-harm will be eighteen, and I’m gonna buy myself a scratch ticket to celebrate.

Thanks for reading; it’s not an easy topic, I know. It’s not easy for people to talk about, and therefore, it’s something I feel like I need to talk about. If one person out there feels less alone in their struggles because of what I write, then it’s worth it.

Take care, and see you again in 2026. May the coming year be kind to you, and full of adventures and peace.