It’s been four years since they died, because time is both nonsense and inescapable.

Four years. The memories come in italics now; softer around the edges, less of a bloodied scalpel excising moments to peer at under the microscope, watching the grief-heavy wounds lay open. They weave in and out of ordinary moments like sutures stitching past to present; I rarely flinch at the piercing anymore. The big days, though – the anniversaries, the birthdays – those still make the scars throb in remembrance.

Four years since I was held in their strong arms, since I whispered I loved them and kissed their forehead. Four years since I rubbed my fingers over their baby duck hair, newly buzzed; four years since they could laugh with delight. I think of all that laughter silenced, all those stories that died with them. They are by no means the origin story of my own writing, but on my dark days, I am reminded of all the stories I carry – Hawthorne’s and Oscar’s and my parents and father-in-law – that may also, one day, die unwritten.

Recently I’ve been frustrated with writing, having trouble with the final edits and the publishing aspect of finishing my current book. Someone close to me, unafraid to ask hard questions in hard moments, reminded me that I have Hawthorne’s stories to finish, too – and my own. The combined taste of frustration and “I love you” is familiar, one we share between us over Hawthorne, who introduced us. I’m forever grateful.

And so, I woke up this morning to write, the still-full moon hanging in my window. It is Mabon, when the days and nights are cleaved in two, a changing of the seasons that heralds the rise of the Holly King. There was a partial lunar eclipse last night, and I felt both the weight of memory and the breeze of Hawthorne’s laughter as I watched the little bite disappear. Hawthorne had been adamant about charging our crystals during a lunar eclipse just before their birthday in their last summer, and so we laid them out on the windowsill at the top of the stairs. On nights like that, with the moon full and glowing, we spoke smugly of the lack of light from streetlamps and local businesses. We reveled in the quiet and dark of our mountain, scoffing at our days in the city, so clearly behind us now. We were never leaving this place where we didn’t have to play “were those gunshots or fireworks?” during the summer (they were gunshots) and there were no neon or LED lights to interfere with the moon.

When the pain from their last surgery didn’t fade, and they struggled to hold on to hope, they cursed themselves for trying to charge the crystals during an eclipse and vowed to never do that again. I’ve kept that vow for them, though mostly unintentionally.

I often wonder if Hawthorne had lived, and been somehow left unchecked, if they would have become a hoarder. They were a collector, a maximalist, someone who could fill an empty space in haphazard form and sit happily in the chaos (until they needed to find their inhaler). When we cleaned, I could hand them a shoebox or a junk drawer full of random, stuffed-in things, and that would keep them occupied for the three hours it took me to clear out six totes old clothes and switch the summer and winter wardrobes. They’d tell me stories that the items represented, or reminded them of, or had absolutely no discernible connection to anyone but themselves – and only in that moment. The thread between the item and stories sometimes never revealed itself again.

I’ll admit it took years for me to get comfortable with this dichotomy of tidying. I know I look back with far more fondness than I felt most of the time. I would be able to empty boxes (for a while, it felt like we were always moving to a new place) and find new homes for things I wasn’t allowed to throw away at a comparatively ridiculous rate while they sprawled on the bed, a box of treasures spread before them. This would happen, too, when we were just tidying the house. One day I removed a small bowl (meant for food) from the windowsill to cries of “no, don’t, I was saving that!” only to look in it and see an empty stem of grapes, a small rock, a guitar pick, and some pistachio shells.

“Why, muppet?” I asked, showing them the bowl.

They peered in and shrugged, their signature sound for “I don’t know” sitting in the air between us until their peal of laughter as they looked up and caught my eye. I threw the contents into the trash bag, squealing “Noooo! Grapey! Rocky! Shelly!” as they laughed harder, tears gathering in their eyes. “P-p-p-picky! Not Picky!” By this time, they were on the floor giggling uncontrollably, braced against the chair they’d been sitting in. I shook my head and put the dish in the sink.

I miss their laugh. I miss their stories, and their music.

Dawn is breaking now, the tallest trees burning with color as pink clouds streak slowly across the sky. Most of the leaves are still deeply green here, but I remember that morning in Vermont. The world was turning gold and amber around us, the remaining greens poised to flame into vibrant yellows and reds. The sun sparkled on the dewy grass, the not-quite frost sliding off at the first rays of light. The sky was sharp and blue, horse-tail clouds distant and starkly white. By the time I stepped outside, there were no other cars in the driveway, those of the first responders pulled over on the side of the road instead. Lucy sat in her stroller, entertaining the half-circle of volunteer firefighters who watched her. The men stood far enough away to be able to claim “not it” for a dirty diaper, and close enough that they would get anything she dropped. She babbled and laughed, and that moment crystallized in my mind.

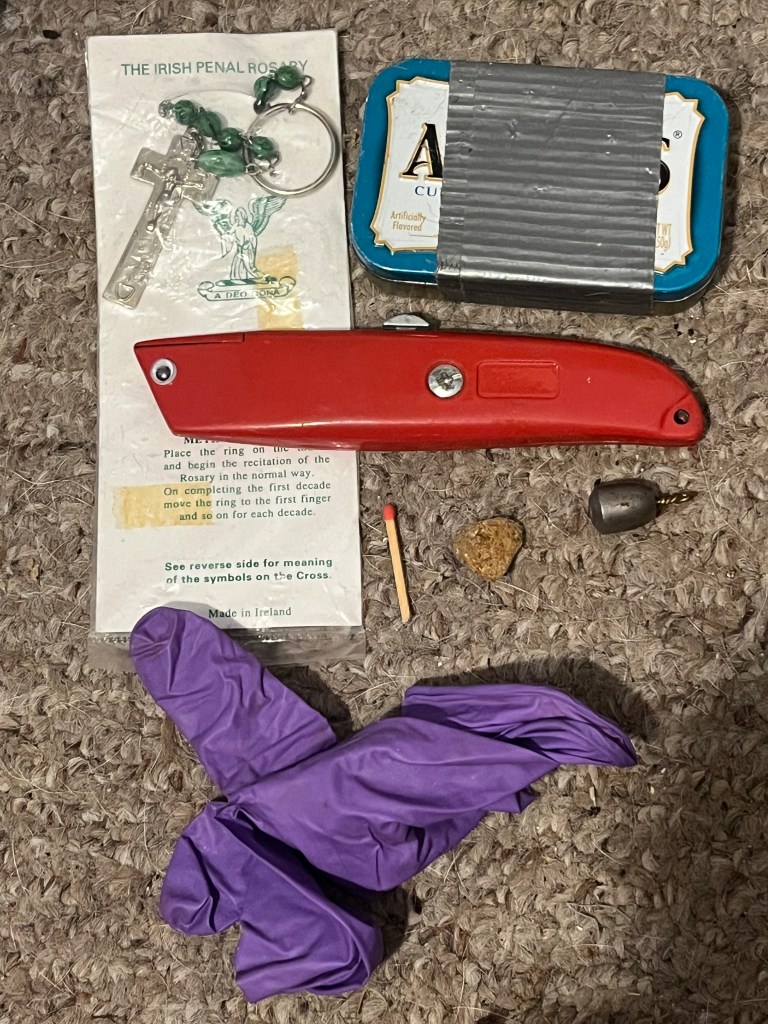

Recently I (finally) cleaned out the toolboxes. I had been meaning to for years, just one of those projects that is always somewhere in the back of my mind (untangling the clump of broken necklaces, hanging up my hats, scrubbing the walls along the stairs where I spilled coffee about knee-height). I put my music on and emptied it, wrench by hammer by screwdriver. I grouped them, then gathered the random hardware – the screws and loose zip ties and washers to who-knows-what. When that was done, I looked back inside; what was left behind could be read like tea leaves.

Hawthorne would have had a field day about this collection here. It would have resulted in hours of stories and laughter, and too many beers. It’s fascinating to me how a handful of random shit could representatively encapsulate them, or at least, the version of them they brought to a shared space with hammers and drill bits. I swear I could create a miniature museum dedicated to my wife, and everything pictured here would be in it, tokens from seasons and phases of their life. They would remind me where the rosary came from that they couldn’t just throw away. They’d talk about JPUSA, and the beautiful girl they fell in love with before being shunned. We would remember EMS stories together, the good and the bad, and the silly flogger they made with a nasal cannula, gloves, and medical tape. They would swim the shark (box cutter) through the air and make up a little song, if Baby Shark hadn’t come out yet. They’d call Ella over, all high-pitched and hysterical, and explain to her that she could not eat this old-ass piece of dog food, but it was OK, they’d go get her a treat (ella had been sleeping until this point). They’d defend keeping a stray match, and they’d want to leave the half-finished toolbox and take the weight and go fishing (we didn’t use weights). They would ask the shark (again, box cutter) to chomp open the Altoids tin, because they couldn’t remember if it was an emergency fishing kit or emergency fire starter kit; clearly it had to be one or the other, as indicated by the stray match and fishing weight. At some point they would have dropped the (BOX CUTTER) and screamed “AH! SWIM AWAY! I DROPPED THE SHARK!”

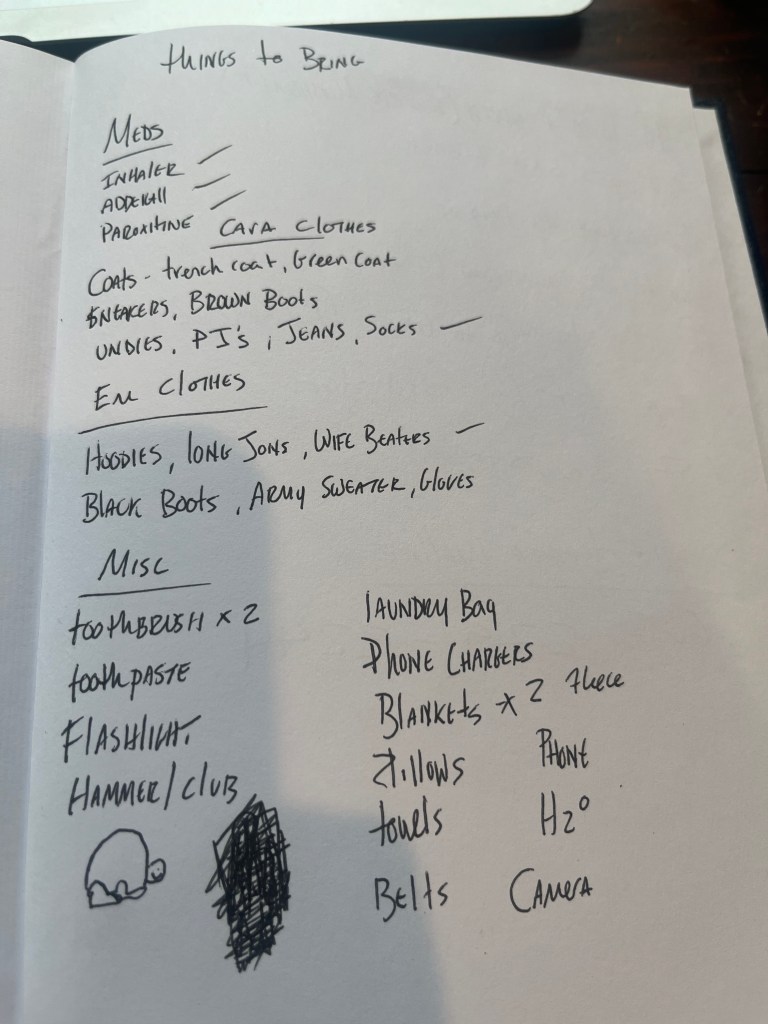

Elsewhere in the house, I still have the drivers’ licenses of two other people that were not me or Hawthorne. There are countless keys and pieces of bike locks that don’t go together. There are lists and half-filled notebooks with turtles and absolutely no concept of how to chemically write H2O.

In which strand of the thread did they live? I want to find the one where Hawthorne woke up without the blinding pain, without the need for 90-proof medicine in plastic handles. I want the one where we went to couple’s therapy and figured out shit out, and bought a place in the mountains to raise our feral child and sheep and chickens. I want the one where I finally got them on a plane, where we went fishing in Alaska, where we vacationed once in Trinidad. I want the one where they never fell down the stairs, where the medical system believed them and treated them appropriately, where they didn’t lose their wedding ring in the river.

I want the one where our memories come back in bold, in large font, in a Spread Eagle Feminist shirt and fist raised. I want the mornings of serving them coffee and first breakfast while they played guitar, eager for the People’s Jam and Heather’s bagels.

I want them to know their kid loves fresh dill on salmon and barely eats bread. I want them to know the laughter of their kid is just as raucous and infectious as theirs, but with less albuterol and more lung power. I want these things that will never happen.

The ink has long since faded from the receipts in their wallet, the thin paper blank and smooth. There are still moments, hours, days that I am angry, days where grief strips me raw so I can do no more than scream at the sea. And it’s okay. I’m not fighting them or trying to get rid of them. They come, and they go.

I’ll take the memories I get and keep them, become the hoarder of their tokens and their left-behinds. I’ll tell their stories, and let their old guitar be played. I have kept the notes and given away the books. I’ve bundled the zip ties and let go of duplicate tools. I’ve kept the pictures and trashed the hat box. I am down to a single box of nostalgia clothes, tucked away in the closet, and I wear their socks in the winter. I might hoard these moments, but I will continue to curate the collection, and let go what no longer brings forward the immeasurable love that we shared.

And fuck knows I’ll be finding these in random places until the day I die.